Taken from Mercury News.

Hiking near wildfire zones? What to know before dashing up that trail

Wilderness experts offer hikers five ways to stay safe from increasing blazes throughout the West

PUBLISHED: | UPDATED:

Dana Hendricks had a front-row seat when 176 hikers got stranded by fast-moving wildfires last year in Oregon’s Columbia River Gorge.

The veteran trail manager who lives just upriver from where it happened said the harrowing episode underscores why those heading into wilderness need to be prepared for a fire. Although all the hikers eventually were rescued, most had to spend a night on a popular trail an hour from Portland after a teenager set off a firecracker that resulted in a wildfire.

While incidents of hikers getting trapped by on-rushing conflagrations are rare, the potential for calamity has dramatically increased with more people venturing into the backcountry where wildland fires are breaking out at an alarming rate as illustrated by recent infernos in Redding and Mendocino County.

“I think it is a new reality for all of us,” said Hendricks, a Pacific Crest Trail regional representative. “If it is not hiking along with a fire it is hiking in recently burned areas.”

More than 4.8 million acres have burned from 37,500 fires in the United States this year, according to statistics from the National Interagency Fire Center. The figure ranks fourth in acreage for the past decade looking at fires from January through July.

How fires can impact outdoor recreation has been on display with the Ferguson blaze just outside of Yosemite National Park.

The wildfire has resulted in levels of particulate pollution in Yosemite Valley exceeding those of Beijing, one of the world’s most polluted cities. It got so bad last week that officials closed some of the park’s most popular sections — the Valley and Wawona. It was the first closure because of fire in almost three decades.

On Sunday, a firefighter died after being struck by a dead tree that fell in the Ferguson Fire area. The incident is a reminder of the dangers of falling debris in scorched terrain even after fire-damaged trails reopen.

Fire and wilderness experts say outdoor visitors need to adjust their habits because the situation is expected to worsen with the impact of climate changes and droughts.

Fires become devilish prey shifting directions without warning and gobbling up the arid landscape with a bottomless appetite.

“You cannot outrun a fire — there is just no way about it,” said deputy chief Scott McLean of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

But those with a burning desire to get outside can do more to ensure their safety. Here are five recommendations for playing in fire country.

Before you go

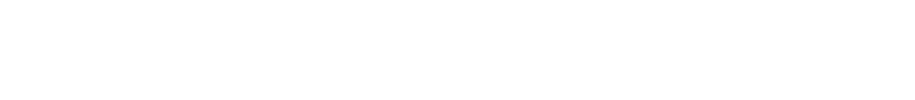

McLean recommends using InciWeb, an online map that shows forest fires across the United States. The National Weather Service offers another platform at California Fire Weather watch.

It’s still a good idea to stop at a local ranger station even after checking the online information. Rangers can help visitors access the risks of specific trails.

The PCT’s Hendricks said officials often close trails if it appears a fire is headed in that direction. Some people, though, ignore the warning because it doesn’t look dangerous to them.

“We still have the problem of folks not taking the closures seriously and that can be one of the most costly and dangerous problems we could have,” said Hendricks, who has worked with the Appalachian Trail Conservancy and American Hiking Society.

What to bring

Hikers don’t need to wear durable Workrite Nomex firefighter pants for a visit to the Great Outdoors. Jeans and cotton shirts will suffice. However, do not wear fabrics made of polyester.

“They will melt and stick to your skin,” McLean said.

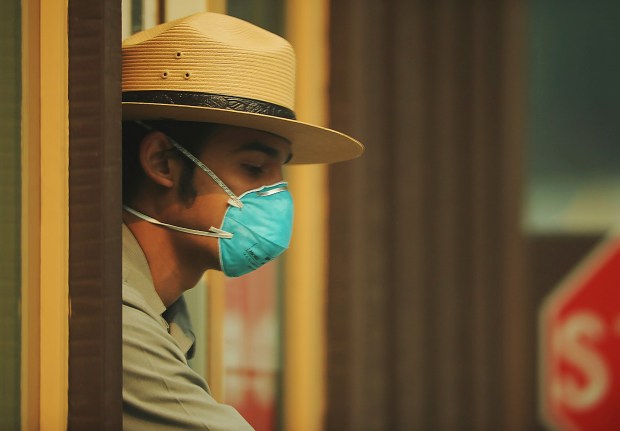

Cotton bandanas serve many purposes but perhaps none as important as reducing the inhalation of smoke. McLean swears by the colorful neckerchief although some experts recommend the N95 or P1000 disposable particulate respirators.

The Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention says to avoid dust masks found in hardware stores. They are designed to trap large particles, such as sawdust. The masks won’t protect lungs from small particles found in wildfire smoke.

Experts recommend people carry what is known as the 10 essentials even on short trips. Among the items listed are a topographic map and compass, which could be life-saving navigation tools when surrounded by flames. A “topo” map is important because it lays out the topographies of the area that will help hikers create an escape route in a dire situation.

Although it is not listed among the 10 “essential” items, a portable shovel also is worth packing for the worst possible situation.

On the trail

After 18 years as a firefighter in remote corners of Butte County, McLean has learned invaluable lessons that he says others need to master when entering the backcountry.

“Once you hike in you need to keep your head on a swivel,” he said. “I’m not trying to scare anybody but you have to pay attention. It’s a lot of what ifs. Don’t be naive, don’t assume.”

McLean wants hikers and others to take mental notes of escape routes to safety zones, which usually are a body of water, but also could be a denuded granite rock area.

As a last resort, trapped firefighters build safety zones composed of bare earth by cutting away vegetation the size of a sheet of 4X8 plywood.

Most hikers can avoid such scenarios by using common sense.

“If you do see smoke, don’t wait,” McLean said. “Don’t assume it is going another way. Leave.”

Smoke signals

Researchers for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency have found that premature deaths from short-term exposure to wildfire pollution averaged from 1,500-2,500 victims annually in the years 2008 to 2012.

If entering an area covered in smoke, stay low to the ground, experts say. The PCT Association reports that air quality is better at lower elevations because smoke rises.

Outdoor enthusiasts also should learn about smoke’s traits to help them predict a fire’s behavior.

When the smoke swirls straight up it indicates little to no wind. If smoke bends in one direction then the fire is pointing to where it is heading.

Smoke likes to travel up the drainages and dirt ravines during the course of the afternoon much faster than in the morning, Cal Fire’s McLean said. However, when the air is cooler and heavier late at night or early in the morning the wind can switch 180 degrees and push a fire back down a canyon.

Watching the smoke’s color can provide clues as to what the blaze might do next.

For instance, white or gray-colored smoke indicates the fire is burning light fuels such as grass or twigs. It usually means the fire will move quickly, McLean said.

Brown plumes suggest it is burning brush whereas dark brown and black means it has ignited oily vegetation or perhaps a structure and would move at a slower pace.

Ring of fire

Like smoke, it is important to know some of the basic characteristics of fire, which, for example, burns uphill faster.

Experts say it is best to travel upwind and downhill when encountering a fire. Avoid canyons, ravines and drainage areas, they say. Hike through streambeds if possible.

“You don’t want to be mid-slope if you see a fire coming” up a ridgeline, McLean said.

But if caught in such a situation the only escape might be descending the dryer side of a mountain, which usually is the eastern slope.

If flames approach while caught outside of a safety zone options often are limited. Experts say the safest place is the blackened earth behind the fire line. Once it is clear the danger has passed it is best to stay on the blackened terrain to get to safety. But watch out for falling debris and unstable ground.

In a dire situation where it is impossible to escape, hikers should find a ditch, gully or streambed without vegetation. An impromptu shelter can be built by digging a hole in the side of the gulley big enough to crawl into — if carrying a shovel.

]McLean said it is best to lie on the stomach with feet pointed in the direction of the fire. Even without a shovel dig a hole big enough for the face to minimize inhaling smoke. McLean suggested covering the face with a bandana and the head with something made of cotton.

The American Red Cross warned against putting wet clothing over the mouth or nose. Moist air causes more damage to airways than dry air at the same temperature, the relief group said.

Others recommend covering the body with dirt.

McLean had one final suggestion for such a situation: “You want as small a footprint as possible,” he said.